What Is a Public Benefit Corporation and How Does It Differ from a Traditional Corporation?

Traditional corporations are built to prioritize shareholder returns. But if your company also wants to serve a social or environmental purpose, a Public Benefit Corporation offers a legal way to do both. In this article, we’ll look at how PBCs work, how they differ from traditional corporations, and why more founders are considering this structure to align profit with impact.

What Is a Public Benefit Corporation?

A Public Benefit Corporation or PBC is a for-profit legal structure available in many U.S. states that allows a company to pursue both financial returns and a specific public benefit. In simple terms, a PBC is a hybrid between a traditional for-profit company and a nonprofit. It makes money like any other business, but it also commits to having a positive impact on society, the environment, or both.

This dual mission is baked into the company’s DNA. When you register as a PBC, you must declare a specific public benefit in your formation documents. That declared purpose becomes a guiding light for the business and a benchmark against which its decisions and progress can be measured.

Under Delaware law, one of the most popular jurisdictions for business incorporation, a PBC must identify one or more specific public benefits in its certificate of incorporation and must operate in a responsible and sustainable manner. The board of directors is required to balance the pecuniary interests of stockholders, the best interests of those materially affected by the corporation’s conduct, and the public benefit(s) identified in the company’s charter. Delaware also requires PBCs to provide shareholders with a statement every two years that assesses how the company is meeting its public benefit objectives.

What Kinds of Purposes Can a PBC Be Incorporated For?

The scope of purposes a PBC can pursue is wide-ranging, and companies typically tailor this to their values, vision, and industry. Common examples include:

- AI Innovation: Advancing AI technologies in ways that are safe, transparent, and aligned with the public interest, ensuring responsible deployment, mitigating risks, and promoting broad societal benefit.

- Environmental Sustainability: Reducing greenhouse gas emissions, promoting renewable energy, conserving natural resources.

- Social Equity: Supporting underserved or marginalized communities, advancing diversity and inclusion in hiring and leadership.

- Health and Wellness: Improving access to healthcare, mental health support, or healthy food.

- Education and Access: Expanding access to quality education or digital tools in underserved regions.

- Ethical Supply Chains: Promoting fair trade practices and ensuring ethical sourcing of materials.

- Community Development: Revitalizing local communities, investing in affordable housing, or creating local employment opportunities.

You can choose one or more purposes based on the kind of impact you want to create. This purpose then becomes part of the company’s identity, governance, and obligations.

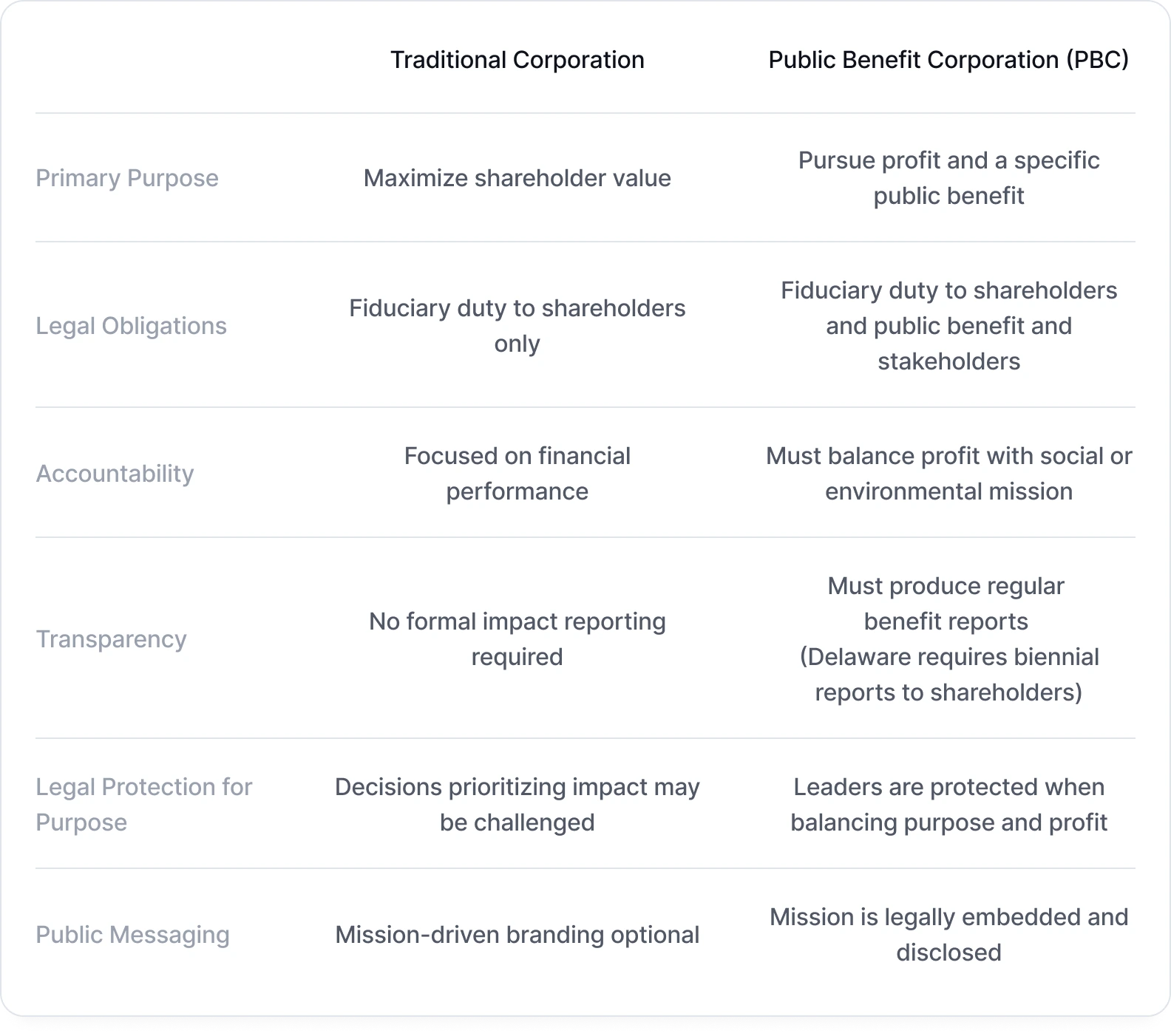

Key Differences from Traditional Corporations

Here’s a side-by-side comparison to help clarify how PBCs differ from traditional corporations:

Transparency and Reporting Requirements

Transparency is a cornerstone of the PBC model, especially under Delaware law. According to Section 366(b) of the Delaware General Corporation Law, a public benefit corporation must provide its stockholders with a report at least once every two years. This statement must include:

- The objectives the board of directors has established to promote the public benefit(s) and the interests of those materially affected by the corporation’s conduct;

- The standards the board has adopted to measure the company’s progress in promoting those benefits and interests;

- Objective factual information based on those standards to show how successful the corporation has been in meeting its goals;

- An overall assessment of the corporation’s effectiveness in advancing its public benefit(s).

While Delaware law does not require this report to be made public or evaluated by a third party, many PBCs voluntarily publish it and align it with third-party metrics. This report not only satisfies legal obligations but also strengthens stakeholder confidence in the company’s long-term mission.

Why Choose a Public Benefit Corporation?

- Authenticity: Your mission becomes part of your legal foundation, not just marketing.

- Investor Alignment: Impact investors often look for companies with legally binding social missions. It signals long-term commitment.

- Talent Attraction: Employees, especially younger generations, are increasingly drawn to mission-driven work. A PBC structure reinforces your credibility as an employer with purpose.

- Stakeholder Trust: Customers and partners are more likely to support a company that transparently commits to doing good.

One high-profile example is OpenAI Inc., which has a unique structure. While the original nonprofit OpenAI Inc. oversees the mission, it also controls OpenAI Global LLC, a capped-profit entity designed to raise investment while staying aligned with the nonprofit’s mission. This hybrid model mirrors PBC principles: financial growth is balanced with a mission to ensure artificial general intelligence benefits all of humanity.

What a PBC Is Not

A PBC is not a nonprofit. It can and should make money. It pays taxes. It can raise venture capital and distribute profits. The key difference is that it also holds itself accountable for more than just profits. It provides a legal framework for integrating social good into business operations without sacrificing financial viability.